Algorithmic Motion Planning Meets Minimally-Invasive Robotic Surgery - Part 2

A Case Study of Inspection Using the CRISP Robot

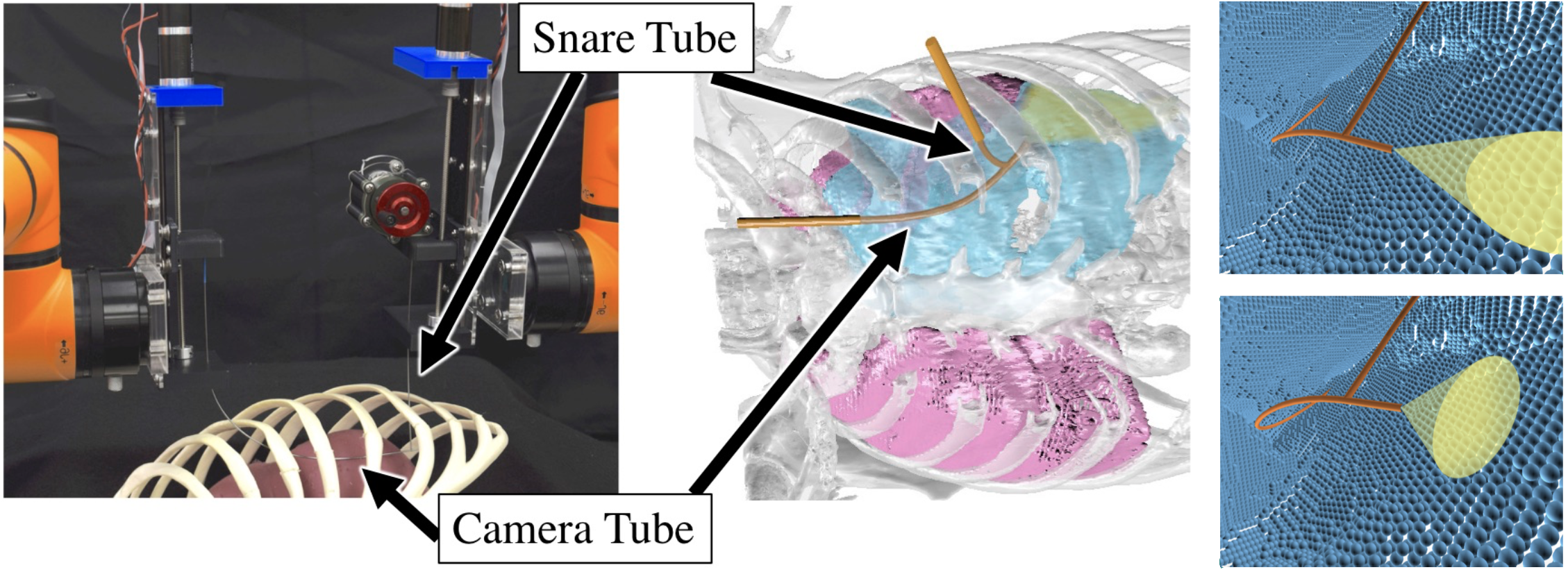

In certain medical applications, physicians may want to inspect some region of interest for diagnostic purposes completing the procedure as fast as is safely possible to reduce costs and improve patient outcomes, especially if the patient is under anesthesia during the procedure. For example, the needle-diameter Continuum Reconfigurable Incisionless Surgical Parallel (CRISP) robot 1 2 was suggested to assist in the diagnosis of the cause of a pleural effusion (a serious medical condition that can cause the collapse of a patient’s lung) by visually inspecting the surface of the collapsed lung and chest wall inside the body3 (see Figure below).

Inspection Planning

This can modeled as an inspection-planning problem where we are given a robot equipped with a sensor and a set of points of interest (POI) in the environment to be inspected by the sensor. The problem calls for computing a minimal-length motion plan for the robot that maximizes the number of POI inspected.

Naively computed inspection plans may enable inspection of only a subset of the POI and may require motion plans significantly longer than an optimal plan, and hence may be undesirable or infeasible due to time constraints. Our goal is to compute kinematically feasible collision-free inspection plans that maximize the number of POI inspected, and of the plans that inspect those POI we compute a shortest one.

What makes it challenging

Inspection planning is computationally challenging because we need to simultaneously reason both about motion planning in a high-dimensional configuration space (the space of all parameters that determine the shape of the robot) as well as about maximizing the number of POI inspected.

There are multiple approaches to computing inspection plans, but here we focus on those that provide some formal guarantee on the quality of the solution. Generally speaking these methods (see, e.g., 4 5) exhaustively search over the space of all motion plans thus guaranteeing asymptotic optimality. Roughly speaking, asymptotic optimality for inspection planning means these methods produce inspection plans whose length and the number of points inspected will asymptotically converge to those of an optimal inspection plan, given enough planning time.

Let’s dive deeper into the term we used earlier “exhaustively search over the space of all motion plans”. To do so, let’s go back to basics and consider shortest-path computation for a while (it may be worthwhile to visit previous posts on motion planning Part 1, Part 2). When we want to compute the shortest path to some point we can use the fact that any sub-path of a shortest path is also a shortest path. Namely, if we know that the shortest path between a and c passes through intermediate point b and we need to consider two paths connecting a and b, then the shorter one will always be better and we can discard the longer one. This is because if we take the shortest path connecting b and c it will always be preferable to append it to the shortest path connecting a and b. This is referred to as Bellman’s principle of optimality.

Going back to our problem of inspection planning this is not necessarily the case. To understand this, assume that we have two POIs and recall our two paths connecting a and b. Assume that the shorter one sees no POI while the longer one sees the first POI. Which one is better? We actually don’t know because it depends on the future: if we consider the first path, then we need to find a path between b and c that sees both POIs while if we consider the second path then we only need to find a path between b and c that sees the second POI.

To summarize, for each intermediate point, we need to consider the trade-off between short paths that see less POI and long paths that see more POI. This set has a name, “The Pareto-optimal frontier”. The set of Pareto-optimal inspection plans is the minimal set of inspection plans such that each plan is either shorter or has better coverage of the POI than any other inspection plan. Unfortunately, computing this set comes at the price of very long computation times as the size of the search space is exponential in the number of POI.

IRIS - Incremental Random Inspection-roadmap Search

To solve the slow running times of existing algorithms, we introduced a new algorithm which we called Incremental Random Inspection-roadmap Search, or IRIS, which is an asymptotically optimal inspection-planning algorithm 6 7. Similar to sampling-based planners1 2, IRIS incrementally constructs a sequence of increasingly dense roadmaps (graphs embedded in the configuration space) wherein each vertex represents a collision-free configuration and each edge a collision-free transition between configurations - and computes an inspection plan on the roadmaps as they are constructed.

Unfortunately, even the problem of computing an optimal inspection plan on a graph (and not in the configuration space) is computationally hard (see discussion above on computing the Pareto-optimal frontier). To circumvent this, we compute a near-optimal inspection plan on each roadmap. Basically, we use the fact that if two paths are “almost the same length” and see “almost the same set of POI”, essentially they are the same for all practical purposes and we can store only one (we have formal definitions for the “almost”s and the “essentially” but theses are out of the scope of this post).

This additional flexibility allows us to improve the quality of our inspection plan in an anytime manner, i.e., the algorithm can be stopped at any time and return the best inspection plan found up until that point. We achieve this by incrementally densifying the roadmap and then searching over the densified roadmap for a near-optimal inspection plan—a process that is repeated as time allows. By reducing the approximation factor (the mathematical tool we use to dictate which paths we consider paths as essentially the same) between iterations, we ensure that our method is asymptotically optimal.

This allowed us to demonstrate the efficacy of our approach in simulation for several complex robotic systems as demonstrated in the Figure above.

For additional details on algorithmic motion planning for continuum robots, see 8 and references within.

References

-

Arthur W Mahoney, Patrick L Anderson, Philip J Swaney, Fabien Maldonado, and Robert J Webster III. Reconfigurable parallel continuum robots for incisionless surgery. IEEE IROS, pp 4330–4336, 2016. doi: 10.1109/IROS.2016.7759637 ↩ ↩2

-

Patrick L Anderson, Arthur W Mahoney, and Robert J Webster III. Continuum reconfigurable parallel robots for surgery: Shape sensing and state estimation with uncertainty. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett., 2(3):1617–1624, 2017. doi: 10.1109/LRA.2017.2678606 ↩ ↩2

-

Alan Kuntz, Chris Bowen, Cenk Baykal, Arthur W Mahoney, Patrick L Anderson, Fabien Maldonado, Robert J Webster III, and Ron Alterovitz. Kinematic design optimization of a parallel surgical robot to maximize anatomical visibility via motion planning. IEEE ICRA, pp 926–933, 2018. doi: 10.1109/ICRA.2018.8461135 ↩

-

Andreas Bircher, Kostas Alexis, Ulrich Schwesinger, Sammy Omari, Michael Burri, and Roland Siegwart. An incremental sampling–based approach to inspection planning: The rapidly–exploring random tree of trees. Robotica, 35(6):1327–1340, 2017. doi: 10.1017/S0263574716000084 ↩

-

Premysl Kafka, Jan Faigl, and Petr Vana. Random inspection tree algorithm in visual inspection with a realistic sensing model and differential constraints. IEEE ICRA, pp 2782–2787, 2016. doi: 10.1109/ICRA.2016.7487440 ↩

-

Mengyu Fu, Alan Kuntz, Oren Salzman, and Ron Alterovitz. Toward asymptotically-optimal inspection planning via efficient near-optimal graph search. In RSS, 2019. doi: 10.15607/RSS.2019.XV.057 ↩

-

Mengyu Fu, Alan Kuntz, Oren Salzman, Ron Alterovitz. Asymptotically optimal inspection planning via efficient near-optimal search on sampled roadmaps. The International Journal of Robotics Research, 42(4-5):150-175, 2023. doi: 10.1177/02783649231171646 ↩

-

Oren Salzman. Algorithmic Motion Planning Meets Minimially-Invasive Robotic Surgery. IJCAI,pp 7039-7044, 2023. doi: 10.24963/ijcai.2023/804 ↩